What’s Stratego?

Stratego; another Milton Bradley produced boardgame (now of course Hasbro) featuring a 10×10 square board and two players with 40 pieces each. Pieces represent individual officers and soldiers in an army. The objective of the game is to simply capture the opponent's Flag (or alternatively, to capture so many of your opponent’s pieces that they cannot make any further moves). What’s brilliant about this game is element of surprise - players cannot see the ranks of each other's pieces, so disinformation becomes a big part of the gameplay. Probably the best 2 player game down to the sheer number of different ways you can play, and the excitement of discovery, as you find where you thought was a flag, was a bomb all along…History

Chinese Predecessors

The origins of Stratego can be traced back to traditional Chinese board game Jungle also known as Game of the Fighting Animals (Dou Shou Qi) or Animal Chess. The game Jungle also has pieces (but of animals rather than soldiers) with different ranks and pieces with higher rank capture the pieces with lower rank. The board, with two lakes in the middle, is also remarkably similar to that in Stratego. The major difference between the two games is that in Jungle, the pieces are not hidden from the opponent, and the initial setup is fixed.

A modern, more elaborate, Chinese game known as Land Battle Chess (Lu Zhan Qi) or Army Chess (Lu Zhan Jun Qi) is a descendant of Jungle, and a cousin of Stratego: the initial setup is not fixed, both players keep their pieces hidden from their opponent, and the objective is to capture the enemy's flag. Lu Zhan Jun Qi's basic gameplay is similar, though differences include missile pieces and a Chinese Chess-style board layout with the addition of railroads and defensive camps. A third player is also typically used as a neutral referee to decide battles between pieces without revealing their identities.

European Predecessors

In its present form Stratego appeared in Europe before World War I as a game called L'attaque. It was in fact designed by a lady, Mademoiselle Hermance Edan, who filed a patent for a jeu de bataille avec pièces mobiles sur damier (a battle game with mobile pieces on a gameboard) on 11-26-1908. The patent was released by the French Patent Office in 1909. Hermance Edan had given no name to her game but a French manufacturer named Au Jeu Retrouvé was selling the game as L'Attaque as early as 1910.

Depaulis further notes that the 1910 version divided the armies into red and blue colours. The rules of L'attaque were basically the same as the game we know as Stratego. It featured standing cardboard rectangular pieces, colour printed with soldiers who wore contemporary (to 1900) uniforms, not Napoleonic uniforms.

Classic Stratego

The modern game of Stratego, with its Napoleonic imagery, was originally manufactured in the Netherlands by Jumbo, and was licensed by the Milton Bradley Company for American distribution, and first introduced in the United States in 1961.

Pieces were originally made of printed cardboard. After World War II, painted wood pieces became standard, but starting in the late 1960s all versions had plastic pieces. The change from wood to plastic was made for economic reasons, as was the case with many products during that period, but with Stratego the change also served a structural function: Unlike the wooden pieces, the plastic pieces were designed with a small base. The wooden pieces had none, often resulting in pieces tipping over. This, of course, was disastrous for that player, since it often immediately revealed the piece's rank, as well as unleashing a potential domino effect by having fallen pieces knock over other pieces. European versions introduced cylindrical castle-shaped pieces that proved to be popular. American variants later introduced new rectangular pieces with a more stable base and colorful stickers, not images directly imprinted on the plastic.

The game is particularly popular in the Netherlands, Germany and Belgium, where regular national and world championships are organized. The international Stratego scene has, in recent years, been dominated by players from the Netherlands.

European versions of the game show the Marshal rank with the numerically-highest number (10), while American versions give the Marshal the lowest number (1) to show the highest value (i.e. it is the #1 or most powerful tile).

For more modern versions including a 4 player Stratego see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stratego.

Setup

Players may arrange their 40 pieces in any configuration on a designated 4×10 section of the playing board. There are also 6 Bombs and 1 Flag, which are not moveable. Note that the moveable pieces have a number in the upper right corner to designate the order of rank. I’m going by the game I was brought up with, thus, the Marshal is ranked 1 (highest), the General 2, the Colonels 3, and so on to the Spy who is marked with an "S".

The players place one piece in each square of their half of the board. All squares are to be filled from each end. That is, 10 per row, 4 rows deep. The two middle rows are to be left unoccupied at the start of the game.

The pieces are placed with the notched ends up and the printed emblem facing the player in such a way that the opponent does not know the arrangement of the pieces. Such pre-play distinguishes the fundamental strategy of particular players, and influences the outcome of the game.

Pieces

For most pieces, rank alone determines the outcome, but there are special pieces. The most numerous special piece is the Bomb, which only Miners can defuse and which immediately eliminates any other piece that strikes it, but cannot move. Each team also has one Spy, which wins when it attacks only the Marshal. The Spy loses if it is attacked by any piece, including the Marshal and except for the opposing Spy, in which case both are removed. From highest rank to lowest the pieces are:

Rank # | Piece | Number available | Special Abilities |

10 or 1 | Marshal | 1 | |

9 or 2 | General | 1 | |

8 or 3 | Colonel | 2 | |

7 or 4 | Major | 3 | |

6 or 5 | Captain | 4 | |

5 or 6 | Lieutenant | 4 | |

4 or 7 | Sergeant | 4 | |

3 or 8 | Miner/Sapper | 5 | Can defuse bombs |

2 or 9 | Scout | 8 | Can move any distance in a straight line |

1 or S | Spy | 1 | Can defeat the Marshal but is defeated by any attacker |

B | Bomb | 6 | Destroys any piece except Miner, cannot move |

F | Flag | 1 | Wins/loses the game when captured, cannot move |

Aim

The goal is to capture your opponent's flag, make him/her surrender, capture all your opponent's pieces, or make it impossible for your opponent to move.Gameplay

Rules for Movement

- Turns alternate, first Red then Blue, one move each.

- A piece moves from square to square, one square at a time. (Exception: Scout – see rule 8). A piece may be moved forward, backward, or sideward but not diagonally.

- Note that there are two lakes in the center of the board, which contain no squares. Pieces must move around lakes and cannot move where there is no square.

- Two pieces may not occupy the same square at the same time.

- A piece may not move through a square occupied by a piece nor jump over a piece.

- Only one piece may be moved in each turn.

- The "Flag" and the "Bomb" pieces cannot be moved. Once these pieces are placed at the start of the game, they must remain in that square.

- The "Scout" may move any number of open squares forward, backward, or sideward in a straight line if the player desires. This movement, of course, then reveals to the opponent the value of that piece. Therefore, the player may choose to move the Scout only one square in his turn, so as to keep the Scout’s identity hidden. The Scout is valuable for probing the opponent’s positions. The Scout may not move and strike in the same turn.

- Once a piece has been moved to a square and the hand removed, it cannot be moved back to its original position in that turn.

- Pieces cannot be moved back and forth between the same 2 squares in 3 consecutive turns.

- A player must either "move" or "strike" in his turn.

Rules for "Strike" or Attack

- When a red and a blue piece occupy adjoining squares either back to back, side to side, or face to face, they are in a position to attack or "strike". No diagonal strikes can be made.

- A player may move in his turn or strike in his turn. He cannot do both. The "strike" ends the turn. After pieces have finished the "strike" move, the player who was struck has his turn to move or strike.

- It is not required to "strike" when two opposing pieces are in position. A player may decide to strike, whenever he desires.

- Either player may strike (in his turn), not only the one who moves his piece into position.

- To strike (or attack), the player, whose turn it is, takes up his piece and lightly "strikes" the opponent’s piece while at the same time declaring his piece’s rank. The opponent answers by naming the rank of his piece.

- The piece with the lower rank is lost and removed from the board.

- When equal ranks are struck, then both pieces are lost and removed from the board.

- A Marshal removes a General, a General removes a Colonel, and a Colonel removes a Major, and so on down to the Spy, which is the lowest ranking piece.

- The Spy, however, has the special privilege of being able to remove only the Marshal provided he strikes first. That is, if the Spy "strikes" the Marshal in his turn, the Marshal is removed. However, if the Marshal "strikes" first, the Spy is removed. All other pieces remove the Spy regardless of who strikes first.

- When any piece (except a Miner) strikes a Bomb that piece is lost and is removed from the board. The Bomb does not move into the empty square, but remains in its original position at all times. When a Miner strikes a Bomb, the Bomb is lost and the miner moves into the unoccupied square.

- A Bomb cannot strike, but rather must wait until a moveable piece strikes it.

- Remember, the Flag also can never be moved.

To End the Game

Whenever a player "strikes" his opponent’s Flag, the game ends and he is the winner. If a player cannot move a piece or "strike" in his turn, he must give up and declare his opponent the winner.

House Rules

Some Are More Equal Than OthersIf two pieces come in contact are of equal rank, the attacking piece wins - this is a great house rule for preventing a slow defensive strategy, and making the game a lot more aggressive (and thus in my experience, more enjoyable. It’s always enjoyable making a ‘perfect’ strike whereby your attacking piece takes a piece of equal value, which in turn makes it gutting when the same happens to you. Makes for some great bluffing too.

Once Spotted, Always Seen

I normally always use this house rule to play. Begin play as normal, but keep the pieces face up for all to see once their identity is revealed. Strong players will memorize the location of all of your important pieces (your Marshal, your General, etc.) anyway, so this is a great house rule to play for quicker play and more energy spent on strategy.

No Poker Face

After each player places their pieces, all pieces are then revealed by turning them face up. Play continues as normal. Or an alternative is for each player to take turns placing each piece face up, one at a time, on any square on their side of the board they choose. Both players are allowed to see where their opponent is placing his/her pieces.

Makes for an interesting game as you immediately know where the enemy Flag is and the strength of your opponent's army – ditto for your opponent.

Rescue Mission

Similar to queening a pawn in chess; twice per game, if one of your officers reaches your opponent's back row, you can rescue one of your ‘lost’ officers. There are these four conditions:

1. Scouts cannot rescue other pieces

2. You cannot rescue Bombs

3. Your second rescue must be with a different piece than your first rescue

4. If you choose not to rescue a piece when that piece reaches the opponent's back row, that piece cannot rescue again

With this variation, you now have the added task of keeping your opponent from reaching your back row.

Bring Mr Flag Home

This is a little twist on the capture-the-Flag theme. All you need is a rook from a chess game to simulate your castle. You play just like the normal game but when the other player captures your Flag and moves away from the space, you place the rook in its position (this is your castle.) So wherever you decide to originally place your Flag in setup becomes your castle. To win, the other player must move with the Flag and return it back to his Flag (or castle if the Flag is already moved from the original position) before he is captured. When he's captured, the Flag stays on the same space and he is removed. The Flags can't be moved by themselves but can be moved by any moving piece by any player to any square. Once an opposing player takes the Flag back to his castle, he wins.

Silent Defence

The attacker has to reveal his rank, but the defender does not. The defender simply declares whether he wins or loses the battle... therefore the attacker is not sure what he was just killed by, or what he just killed.

This is one of the published variations from the rule booklet in the later versions. This probably came about from the electronic version in the 90s which plays by a similar rule. In Silent Offense, the opposite is true. The attacker asks for the defender's rank. The attacker then declares who is the victor.

True Assassin

The Spy can capture any officer as long as it the one attacking. I love playing by this rule, in fact I feel it ought to be the default rule because this variation makes the Spy a much more significant player. With the classic rules, as soon as the Marshals are eliminated, the Spy is all but worthless. It's only role would be that of a scout to find out the value of an opposing piece.

Attacking Scout

The Scout piece can strike on a long move. This gives the Scouts more power, and can add a bigger danger threat to solid arrangements. I love playing with this rule because along with the Assassin rule, it adds more excitement and a kind of ‘fair play’ tactic to these special pieces.

Tactics

Collecting the information, planning, and strategic thinking play an important role in Stratego, especially the psychological aspects of it. Although I will show some brilliant tactics, they are never quite full proof because your opponent could play the same tactic against you! Also note, tactics drastically change depending on the house rules you play. I will bring your attention to this further in the specific tactics.

Famous Five Strategies

1. Placing one's pieces initially so as to protect the Flag, while possibly misleading the opponent as to where it is

2. Make strong pieces available for attack; don’t hide them trapped in corners or behind bombs as you may disadvantage yourself by not having the chance to use them.

3. Identifying patterns in the enemy's movement during game play that give clues as to the distribution of the opponent’s forces.

4. Starting with stronger pieces and/or Bombs farther away from the Flag (although this is risky), so as to trick one's opponent into attacking the wrong side of the board.

5. During game play, players must identify Bombs without sacrificing too many troops, determine the probable location of the enemy Flag, and form an attack plan that takes into account the likely ranks of the troops and exact location of the Bombs that usually surround the Flag.

Flag placement

Since one of the win criteria is to capture the Flag, its placement is vital. It is commonly placed on the back row surrounded by two or three Bombs for protection. Some players will use this generalisation to their advantage and place the Flag somewhere unprotected, for example the Shoreline Bluff (also called "the Lakeside Bluff"), i.e. placing the Flag directly adjacent to one of the lakes where the opponent may not think to look for it.

Inexperienced players may accidentally alert an opponent to the location of their Flag by calling too much attention to it when they initially position their pieces on the board. This is often done by simply placing their Flag down first and then constructing their defenses around it. One counter measure for this is to place all the pieces on the board randomly and then rearrange them into the desired setup. This tactic became obsolete when some newer versions came supplied with a cardboard privacy screen.

Calling Bluffs

A cluster of Bombs may deceive one's opponent into thinking they know where the Flag hides, when in fact, it is on the other side of the board.

Threaten with a small unit, towards a known medium sized unit, convincing your opponent to think your piece is much more powerful, and thus they retreat.

If the opponent's Marshal wins its first battle (and is thus revealed), and a player immediately moves a piece near the back row on the other side, the opponent will probably assume that this piece is the Spy when, in fact, the Spy may be on the other side of the board (and already close to the Marshal). This is a common tactic as it may cause the Marshal to move next to the Spy, thereby allowing the spy to attack first.

Scouting for Flags

Scouts are very useful towards the end of the game, once the board clearer. They can be used to identify bombs on the back row, reveal bluffs or even capture the flag (if your rules permit). They are most effective when they are moved one space at a time until necessary, as the moment they move multiple spaces, they are identified as a scout. Since they can move along a whole line, they are also effective for catching a spy daring to take a step into one's territory, even when they are standing on the other side of the board.

Secret Spy

Placing the Spy too far forward, for example, makes it more likely to be captured early on, but placing it too far back may make it inaccessible when the enemy Marshal is identified. In most games, it is advisable to have the Spy shadow a General or a Colonel. These pieces are normally vulnerable to attack by the opposing Marshal. Keeping a General or Colonel in the same vicinity as the spy allows an effective retreat to where the opponent's Marshal can be ambushed by the Spy.

Spy bluffs are also effective. For example, using a Sergeant to shadow a Colonel might confuse an opponent, and he may be reluctant to have his Marshal attack the Colonel.

Bombs Ahoy

Miners are weak, but their ability to defuse Bombs may be needed early, although sophisticated players might identify opposing Bombs, but leave them in place, interfering with the enemy's movement. To do this, it is vital to memorize the location of all the opponent's Bombs as they are identified. By keeping the Miners unmoved in his own territory during the early game, a player can create the Bomb bluff, in which the opposing player may mistake those unmoved Miners for Bombs.

Perfect Strike

One of the most important concepts of Stratego is the incomplete knowledge and misdirection, so the manual recommends taking a piece with one that is not much stronger than it, for example strike a Captain with a Major. In the same manner, one strategy is to protect with an "evens and odds" system, where a piece is protected by one two levels stronger than it, an odd piece protecting another odd piece, for example protecting the Captain with a Colonel.

Queen of Chess

Just like in Chess, if a player is lucky enough to have gained an advantage over his opponent, they should not hesitate to sacrifice their Queen for the greater good. For example, attacking a Major with another Major is much more of a loss for the opponent if he doesn't have any Colonels, Generals or Marshals remaining on the board.

Unknowingly Unknown

A risky strategy, (all the more exciting) which might be necessary when losing, is to attack unknown, unmoved pieces with a strong piece. This strategy relies on odds, for example if a player attacks an unknown, unmoved piece with a General, it would lose to any of the 6 Bombs, the Marshal or the other General. Mathematically, the odds are 7 in 40, but realistically these can be improved by not attacking pieces likely to be Bombs, or by keeping track of the pieces already identified.

My Ultimate Arrangement

Taking into account this strategy is played when the following house rules are in play:

- Some Are More Equal Than Others

- Once Spotted, Always Seen.

- True Assassin

- Attacking Scout

(See House Rules for more information)

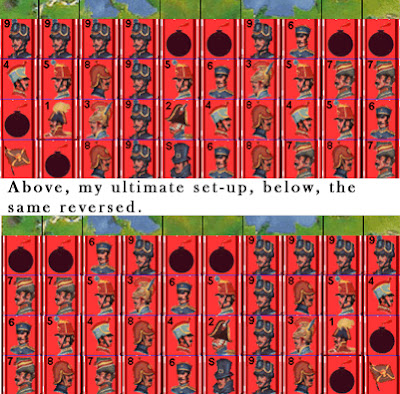

By positioning your pieces in such a way as shown;

1. Play by using the scouts to seek out your opponents side - first use the scout nearest to the lake (it increases your chances of discovering a ‘tricky’ piece, as I will later explain). This is where the Attacking Scout house rule comes in real handy as if they also have scouts on their front row, you’ll (assuming you go first) be able strike them out. This then means they either reveal themselves to you as they take your Scout, or, better still, they leave your Scout for that turn, which means on your turn you can use your scout to see a trickier piece, that’s a piece hidden behind the lake.

2. Continue using scouts until it is no longer possible to seek out a piece without being caught first. Due to the Attacking Scout house rule, if your opponent takes one of your scouts with their own, your set-up is created so you can take their piece with another Scout! Make sure to move scouts into positions where they can be used on the next turn, if you are taken, of if you move to the side revealing a pathway for you to check out another piece.

3. Now use the Five or Four (That’s a Major or a Captain, as I’m using the American numerical ordering whereby #1 = the best piece, The Marshall) depending on the front/second row strength you’ve discovered, so if you reveal eights to sixes play your five, if you reveal five, play your four, and of course if you find a bombs use your eight. This is your side for ultimate attacking, the other sides are merely a distraction for your opponent, and should only be played for defensive reasons.

4. Once you break through your opponents first two rows of defense you are bound to come across some high ranking officers. That’s where, depending on what you see (use your scouts damn it!) you will use your Colonel (3) to take definite pieces (those you know are safe to take, without fear or repercussions).

5. Try to drag out your opponents pieces, using the bluffs and poker face tactics I’ve described before. Sacrifice your Colonel even if it means taking a General (2) or a Marshal (1).

6. If you come across a Marshal early on, it will become a cat and mouse game, hopefully they will come down to greet your hidden Marshal, but if they are content on staying put your going to have to trap their one by bringing out your spy.

7. At some point your other rows will be broken into, and hopefully you will have done plenty of defense damage simply with the order of the units. The side furthest away from the flag is the weakest, with just a Colonel for protection, so if a General or Marshal comes out to play down that row, there isn’t much you can do, but don’t fear because they will not be able to get to your flag since your spy and two defend the middle part, and of course your Marshal defends the flag side.

8. With plenty of practice this set-up will become a near perfect win every time, in fact I have never been beaten by a player or by the computer with this set-up, HOWEVER, note that this set-up works only if playing by the house rules laid out before. Without them, then this not as strong, in fact it could be quite damaging depending on which rules you play by.

For other great set-ups I suggest you browse Ed Collin’s blog dedicated to Stratego, or play online Sean O’Connor’s The General, (which is exactly like the board game, complete with house rule options) which has a range of different set-ups that you can test for yourself.

Sources

Sites

www.edcollins.com/stratego/ en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stratego